The recent changes are:

- Feeding ractopamine to make animals leaner.

- Growing and fattening cattle more quickly to reach market weight by 20 months for the export to market.

- Feeding wet grain products from ethanol plants. This can be ruled out because this feed was not available during the summer of 2006 in the area where the feedlots were located.

- Since 2006 there have been additional reports of heat stress in some cattle that are fed beta-agonists.

In the summer of 2011 I observed fed steers arriving at a plant in over 100 degrees F (38 degrees C) temperatures with severe heat stress and stiff type lameness. These animals walked with a stiff hesitant gait and were definately clinically lame. The percentage of lame steers varied from 5 to 10% on a truck load to 50%. Some animals had open mouth breathing. The hooves had no signs of pathology such as foot rot. It is highly likely that the lameness and open mouth breathing was related to an unknown dose of either Ractopamine or Zilpaterol, which are beta-agonist drugs used for growth promotion. All steers were unloaded promptly at the plant.

Research conducted by Kurt Vogel at Colorado State University as part of doctoral dissertation has shown that certain combinations of beta-agonists and hormone ear implants increased heat stress while other combinations reduced it. In steers, Zilpaterol combined with a Revelor implant was a safer treatment from a heat stress standpoint compared to Zilpateral alone. When Ractopamine was fed, the opposite effect occurred. Ractopamine alone increased susceptibility to heat stress. Difficulty mixing small amounts of beta-agonists into the feed may explain why the beta-agonists used in this study had little effect on weight gain. In the meat plants, I have observed odd, uneven effects where a small percentage of the cattle were severely heat stressed and lame and the others were normal. Official feed testing parameters from the manufacturers of beta-agonists have a wide range of permissible error from 125% to 75% of the correct dose. A single initial feed test showed that the dose was low in our study. Handling the cattle frequently may also have had an effect on the lack of weight gain. This is very preliminary data and this experiment will need to be replicated. Due to a severe illness, some of the feed samples that should have been collected by feed lot management to monitor the dose was not collected. It was important to get information out on the possible beta-agonist/implant interactions and their effect on heat stress.

I recommend measuring outcomes instead of inputs. Fed feedlot cattle that arrive at slaughter plants should be scored for lameness and heat stress symptoms. Feedback should be provided back to the feedlots so that the problem can be corrected. Terry Mader from the University of Nebraska states that when cattle are open mouth panting they have severe heat stress. The first symptom of heat stress is drooling. Cattle that show signs of heat stress must be provided with either sprinklers or shades. When normal cattle breath, the head will remain still. When they are in a pre-heat stress state, their heads will start to bob up and down. Cattle that start to head bob should be carefully watched for further signs of heat stress.

April 2013 Update: Welfare problems observed in feedlot cattle arriving at slaughter plants that have been fed beta-agonists

The author has observed more problems in fed cattle arriving at slaughter plants which had been fed beta-agonists. In most cases where bad effects are observed, the effects were uneven. A few animals were severely affected, 20 to 50% were sore footed lame, and the rest of the group were normal. I have observed this in these types of cattle: Holstiens, Brahman X British X Continental cross steers, and in groups of cattle that were all Bos Tauras beef breeds with no signs of Brahman characteristics.In hot weather, 95 degrees F (35 degrees C), the severerly affected animals had open mouth panting and a few animals became non-ambulatory. The lame cattle were sore footed on all four feet and they were reluctant to walk quickly down the truck unloading ramp. Normal cattle will run or trot down the ramp. During cooler weather, stiffness has been observed in steers fed Zilpaterol. They act like they have muscle cramps. I have observed one group of cattle fed Zilpaterol that walked normally. They came from a feedlot with a sophisticated mill that would have mixed the feed evenly. There has also been a report of a "statue steer" which walked off the truck and when it was time to be moved to the slaughter line he stood and refused to move. He acted like he was too stiff or sore to move. These observations indicate that there are severe welfare problems in some animals fed beta-agonists. Poor feed mixing may be part of the problem. Cattle arriving at the plant should be evaluated for lameness, heat stress (open mouth breathing), and stiffness. From an animal welfare standpoint, lameness, open mouth breathing, and a stiff gate are not acceptable.

There is also a need for research on a genetic interaction and beta-agonists. I observed a pen of cattle that contained many different breeds. A Simmental steer had become very big and stiff and a Hereford steer appeared more normal. Possibly cattle with a greater genetic potential for muscle growth have more effects.

April 2014 Update

Research by Guy Longeragan at Texax Tech University and Dan Thomson from Kansas State University indicates that both ractopamine and zilpaterol increase death losses in feedlot cattle. There problems are most likely to occur during hot summer weather. The study also indicated that in steers fed zilpaterol, dark cutters increased form 0.53% of the cattle to 1.59%. The entire paper can be downloaded for free.February 2018 Update

New research on the effects of beta-agonists on mobility (lameness) in cattle indicates that problems with compromised animals increase as the cattle move from the feedlot to the abattoir (Hagenmaier et al, 2017a). All of the problems I had previously observed in cattle fed beta-agonists ocurred when they arrived at the slaughter plant. The temperature was over 32 degrees C (90 degrees F). Both Basczak et al (2006) and Woiwode et al (2013) saw no adverse effects of feeding beta-agonists during handling at the feedlot. The cattle in Basczak et al (2006) were fed ractopamine at a dose of only 200 mg/day.Both cattle and pig studies show that high doses of beta-agonists and aggressive handling will cause problems (Hagenmaier et al (2017), Peterson et al (2015), Ritter et al (2017), James et al (2011), Puls et al (2015)). Hagenmaier et al (2017b) fed ractopaminefor 28 days at a dose of 400 mg/day. The maximum temperature was 32 degrees C, when the cattle arrived at the abattoir. The controls had 6% of the arriving animals lame and the ractopamine group had 22%. P value 0.09. There were 84 cattle per treatment. After six hours in the lairage the controls had 23% lame and the ractopamine cattle had 17%. P value of 0.43. A possible reason for the odd result is that half the cattle were subjected to either high or a low stress handling prior to loading for the feedlot. Both groups had to move through a 1500 ft long alley. The high stress group was forced to trot. The results section of the paper did not specify the percentage of lame cattle by handling treatment. Possibly animals that were forced to trot developed stiff muscles after resting.

Lameness was assessed using a four point scale. It was scored during either truck unloading or movement out of a pen (Edwards et al (2017)). Lameness scoring:

- = Normal

- = Keeps up with normal walking cattle; slight limp or stiffness

- = Lags behid normal walking cattle

- = Extremely reluctant to move

There was an extreme case where the hoof shells fell off of 17 fed beef cattle when they arrived at the slaughter plant (Thomson et al, 2013, Hoffstutter and Polansek, 2013). Industry sources informed me that they had been fed zilpaterol and a very high concentrate diet. I have worked with fed beef cattle at the abattoirs for over 30 years. I have watched thousands of cattle moving through lairages in multiple plants. I have never seen a hoof shell fall off or heard about a foot falling off until beta-agonists came on the market.

When beta-agonists first came on the market I started seeing fed cattle arrive at the abattoir that acted like they had stiff muscles. The best way to describe these animals is that they acted like the lairage floor was red hot. Cattle in the pens often shifted their weight back and forth. Both my own observations and reports from people working in the lairages indicate that temperatures over 35 degrees C (90 degrees F) are when the lameness problems greatly increase.

A study by Stackhouse-Lawson et al (2015) supports the idea that the cattle have sore muscles. Feeding zilpaterol increased the occurrence of cattle lying in the full lateral position. There was also more agonistic pushing and mounting behavior (Stackhouse-Lawson et al, 2015).

For cattle, both the scientific literature and reports from people working in lairages indicate that the combination of high dose beta-agonists and hot weather, increase problems with stiffness and lameness. Both pork and beef studies show that physical exertion and rough handling can increase problems. From a welfare standpoint, the sensible approach is to use the NAMI (2015) four point scoring system to access fed cattle arriving at abattoirs. In beef cattle, hot weather is more likely to cause problems. The bottom line is that lower doses and careful low stress handling may sovle welfare issues. Cattle unloading from a truck at an abattoir should be able to walk normally.

November 2018 Update: Lameness continues to be a problem

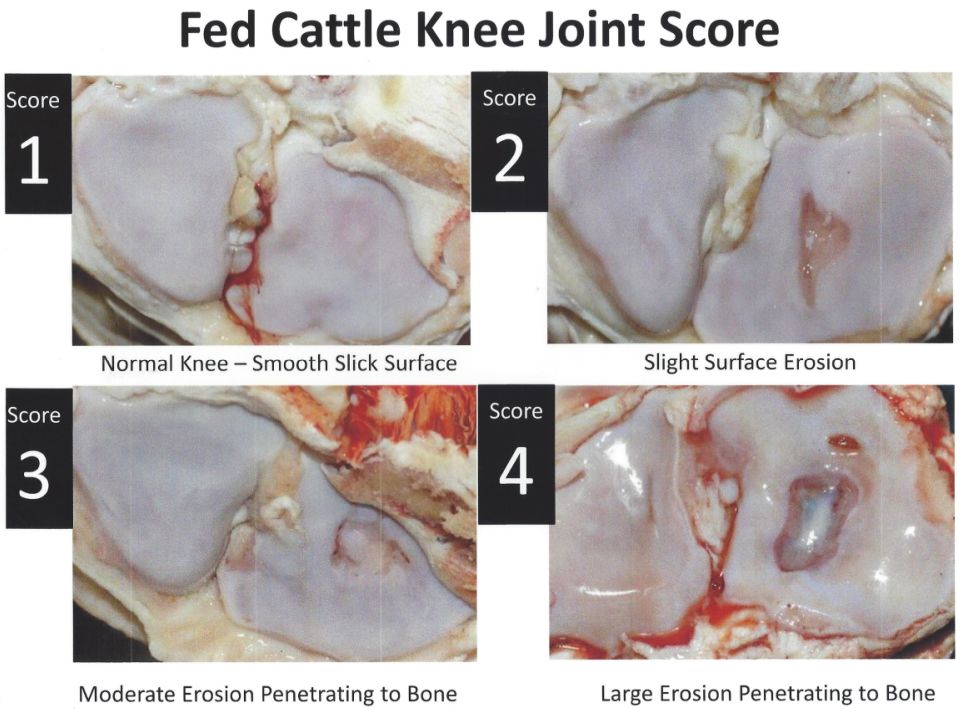

During the last year it appears that additional factors may be contributing to lameness in fed bee cattle. Scott Crain, a veterinarian in Kansas, has been scoring knee join terosions in fed cattle. Below is a scoring chart that can be used at a slaughter plant to assess knee joint damage. The photos are by Scott Crain.

A score of 1 is a normal knee joint with a smooth slick surface. A score of 4 has a large erosion that penetrates the bone. Preliminary observations by Dr. Crain indicate that natural cattle that have never received either beta-agonists or growth promoting hormones also have signs of joint damage. The joint damage in the natural cattle is less severe.

The additional factors that may be contributing to joint damage and lameness are:

- Heavier weights at a younger age

- Leg conformation problems associated with indiscriminant selection for carcass traits. In the late 1980's and early 1990's the pork industry had serious problems with lame pigs due to poor leg and ankle conformation. The author has observed that problems with downed non-ambulatory pigs were greatly reduced when pork producers stopped using a boar genetic line with poor legs. To prevent lameness the Angus Association in the U.S. now has guidelines for leg conformation. Vollmar (2016) reported that cattle originating from ranches in the Northern U.S. were more likely to have the crooked claws hoof defects compared to cattle from Texas. This is possibly due to the more intensive breeding programs at the larger northern ranches.

September 2024 Update

- Problems with twisted claws that can cause lameness are becoming worse. In 2023 I observed some groups of Angus cattle that had crossed crooked toes. A veterinarian working with cow calf producers has observed that it may be more likely to occur in Angus calves selected for high weaning weights. It is definately associated with genetic selection. Good scoring tools are available in Sitz et al (2022).

- Feeding diets with excessive levels of concentrates. The animals may be being pushed too hard with high concentrate ratios.

- Feeding cattle for long periods on concrete slats. Wagner (2016) found that cattle housed on bare concrete slats had increased swollen knee joints compared to slats covered with rubber. In the 1970's, the author observed that cattle housed for 100 days or less on bare concrete slats had knee joints with a normal appearance. It appears that the time housed on the concrete slats is a factor. Heavy 539 kg cattle placed on concrete slats were free of adverse effects (Bernadette et al, 2017). Elmore et al (2015) also reported that rubber mats reduced joint swelling. Reducing the number of days that cattle are housed on slats will reduce joint swelling.

- Congestive heart failure is increasing in grain fed heavy cattle. It may be associated with late stage death I. Kukor et al (2021) reported that 20% to 35% of fed cattle had swollen hearts. Another study at the Simplot feedlot by Buchanan et al (2023) also found high percentages of swollen hearts. Fat steers with heart issues may appear to have pneumonia and be sluggish. Heart problems are associated with certain sires and selection for economically important meat traits. Both crooked claws and congestive heart failure are serious animal welfare issues. Cattle should be selected that do not have these traits.

Next Steps for Research

To calibrate the knee joint scoring chart, a study should be conducted to compare knee joint erosion scores to lameness scores. Further studies to compare visual erosion scores to histology would also be helpful. Observations by the author and internal industry data indicate that there are high percentages of cattle that walk normally. The major problems are occurring in cattle originating from particular feedlots that are easy to identify.

References

Bernadette, E. et al, 2017. Effect of concrete slats, three mat types, and out wintering pads on performance and welfare of finishing steers. Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica. 59:34.)Buchanan, J.W. et al 2023 Variance component estimates, phenotypic characterization, and genetic evaluation of bovine congestive heart failure in commercial feeder cattle. Frontiers in Genetics 1148301

Basczak, J.A. et al, 2006. Effect of ractopamine supplementation on behavior of British Continental and Brahman crossbred steers during routine handling. Journal of Animal Science. 84:3410-3414.

Elmore, M.R. et al, 2015. Effects of different flooring types on the behavior, health, and welfare of finishing beef steers. Journal of Animal Science. 93:1258-1266.

Hagenmaier, J.A. et al, 2017a. Effect of ractopamine hydrochloride on growth performance, carcass characteristics, and physiological responses to different handling techniques. Journal of Animal Science. 95:1977-1992.

Hagenmaier, J.A. et al, 2017b. Effect of handling at the time of transport for slaughter on physiological response and carcass characteristics in beef cattle fed ractopamine hydrochloride. Journal of Animal Science. 95:1963-1976.

James, B.W. et al, 2011. Effects of dietary L-carnitine and ractopamine HCL on the metabolic response to handling in finishing pigs. Journal of Animal Science. 91:4426-4439.

Kukor, I. et al 2021. Sire differences within heart and heart fat score in beef cattle. Translational Animal Science 5(Supplement S1):S149-S153

Longeragan, G.H., Thomson, D.U., and Scott, H.M, 2014. Increased mortality in groups of cattle adminstered B-Adrenerger-agonists ractopomine hydrochlonde and Zilpaterol hydro chloride PLUS ONE. 9(3)39117.doi:10.1371/jurnal/pone.0091177.

Peterson, C.M. et al, 2015. Effect of feeding ractopamine hydrochloride on growth performance and responses to handling and transport of heavy weight pigs. Journal of Animal Science. 93:1239-1249.

Puls, C.L. et al, 2015. Impact of ractopamine hydrochloride on growth performance, carcass and pork quality characteristics, and responses to handling and transport in finishing pigs. Journal of Animal Science. 93:1229-1238.

Ritter, M.J. et al, 2017. Review: Effects of ractopamine hydrochloride (Paylean) on welfare indicators in market weight pigs. Translation of Animal Science. 1:533-558.

Sitz, T. et al 2022. Importance of foot and leg structure for beef cattle in forage based production systems. Animals, 13, 495.

Stackhouse-Lawson, K.R. et al, 2015. Effects on growth promoting technology on feedlot cattle behavior in the 21 days before slaughter. Applied Animal Behavior Science. 162:1-8.

Thomson, D.U. et al, 2016. Description of a novel fatigue syndrome in finished feedlot cattle following transportation. Journal of American Veterinary Medical Association. 247:66-72.

Vollmar, K., 2016. Survey of prevalence of conformational leg defects in feedlot receiving cattle in the United States. Masters Thesis, Colorado State University.

Wagner, D., 2016. Behavioral analysis and performance responses of feedlot steers on concrete slats versus rubber slats. ASAS/ADSA Joint Annual Meeting (Abstract). July 22, 2016, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA.

Woiwode, R. and Grandin, T., 2013. Field study on the effect of zilpaterol on the behavior and mobility of brahman cross steers at a commercial feedlot. Final report to National Cattleman's Beef Association, Englewood, Colorado.

Click here to return to the Homepage for more information on animal behavior, welfare, and care.

Click here to return to the Homepage for more information on animal behavior, welfare, and care.

Click here to return to the menu of animal welfare guidelines.

Click here to return to the menu of animal welfare guidelines.